I wrote this paper a while back. I’ve edited (recently) for clarity and for helping understand some literature on the subject of principal agent problems. I recently wrote a post about applying the principal agent problem to leadership broadly. I wanted to expand upon the literature, and from this, explore more game theory on this blog.

Many people in the construction industry recommend hiring an inspector after employing a contractor. After all, its rational to be afraid that a contractor would “cheap out” and use subpar construction materials because they suspect you wouldn’t know they did, allowing them to turn an easy profit.

This example and thousands of others showcase the principal-agent problem in action. The principal-agent problem is a situation in which one person (the agent) can make decisions for another person or group (the principal) on their behalf, but the lack of symmetrical information encourages the agent to act in their own best interests as opposed to the principal’s.

Asymmetric information poses a challenge to accountability, promoting moral hazard. The concept of moral hazard means that the actor is less likely to engage in good behavior because the incentives for doing so are less strong than before. In the case of asymmetric information, it’s hard to punish those who take advantage of a system, which encourages people to do so. Particularly opaque situations may be more prone to bad behavior because it can be hard to tell whether it exists.

“Game Theory” suggests that in circumstances where the agent’s interests are not aligned with the principal’s, the agent will likely act according to their own interests more than following the directives or goals of the principal. Despite the challenges of asymmetric information, incentives may be able to be put in place to encourage good behavior (or may not be). Economic literature on the subject is mixed about the effectiveness and pervasiveness of this challenge.

Principal Agent Problem Examined in Volunteering on Political Campaigns.

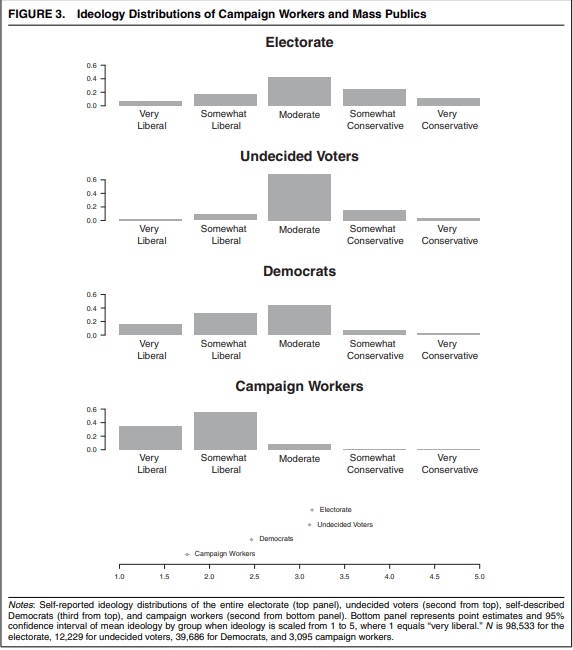

The principal-agent problem can show up in many surprising places. The year is 2012, Ryan Enos and Eitan Hersh are examining the dynamics associated with Barack Obama’s campaign, curious about whether campaign volunteers (agents) are effective intermediaries between candidates (principal) and voters. Demographic information suggests that the Obama campaign struggled to attract volunteers who would communicate issues that most voters could connect with. Since campaign workers have different electoral priorities than voters, (they tend to be a lot more ideological for instance) they struggled to be effective as an advocate for the campaign. A graph from the paper is below.

Particularly striking was the difference in most important issues between volunteers and voters. Inequality was 23% of campaign workers’ most important issue followed by education. Yet, undecided voters saw neither of the two as being within the top five most important issues. This meant that canvassing had a widespread convincingness conundrum, likely costing votes in swing states.

Looking at the ideology of campaign workers juxtaposed with undecided voters in Ohio, one might observe that undecided voters had large proportions in the “moderate“ and “somewhat conservative” categories while most campaign workers were in between the “somewhat liberal” and the “very liberal” categories. Making matters worse (for the candidates), out-of-state campaign workers were even more detached from the point of view of in-state workers, further weakening the effectiveness of canvassing. (Enos & Hersh 17).

I’d recommend checking out the paper if one is interested in empirical political science about the effectiveness of canvassing. Some limitations of the paper include having no way to quantify enthusiasm and effectiveness of campaign workers despite their biases. This also is not comparative, suggesting that the average Republican campaign may not suffer from this issue because of different demographics for instance. Overall, worth thinking about.

Corporate and Social Entities Experiences with the Principal-Agent Problem

Game theory applied to the informal dynamics of power might provide insight into the way that corporations and other social entities are structured. Instead of currency, power itself may be used to achieve goals. For instance, spousal hires are often not repaid with money, but rather with increased discretion (Li, Powell, 2). This style of future benefit serves as an explanation for many businesses that crumble under the weight of their previous successes.

If good decisions today mean more power later, organizations may have trouble maintaining their successes as the organization increases the amount of power associated with the employee to the point that the employee can no longer be punished. This may explain why good ideas are often quashed, and bad ideas are able to survive even when its publicly obvious that there is no longer a perceived strong reason to maintaining the current course of action.

A particularly insightful aspect of the paper argues that time horizons affect what is considered rational for managers. The paper suggests that good decision making by managers may ultimately create entrenched yet inefficient power structures. After all, the process allows “Subordinates to make good use of whatever power they have today, but … only by allowing them to abuse their power in the future” This implies that there’s a bounded view on good decision making, and boldly claims that perhaps a second-best approach may provide the highest expected payout.

This paper is significantly more theoretical than the first, switching the focus from the empirical. Seeing the ways that applied business research intersects with economics is interesting and the insights to this paper suggests that institutions gradually fail. This is a subject I hope to explore more in the future. Anyways, one weakness to this experiment is that lacking empirical data, it seems hard to make falsifiable many of its claims, and primarily looks at one agent principal-agent situations, which may have different assumptions that multiple agent interactions.

Political Challenges Associated with Principal-Agent Problem

The principal agent problem also shows up when dealing with government agencies. James Buchanan, a trailblazer in the practice of public choice examines tax reform in his paper to describe why constituency gains can often be limited by agent’s discretion within the government.

. It is in the interest of the constituency to have a stable tax policy for the purpose of decreasing transition costs and allowing business to be primarily distorted. However, political agents have the goal of maximizing their own rents and look to ways of cloaking policies that fail to achieve constituency, or principality’s goals. The example brought up in his paper deals with the tax legislation of 1986.

The idea was to reduce rates, and broaden the base, and theoretically this was sold as something that could be overall welfare increasing to society (Buchanan 30-32). Instead of having certain activities encouraged or discouraged, investment would be able to flow towards the most productive activities. On its surface, this looked good, however political agents merely used this reduction as an excuse to increase the overall burden of taxation. Instead of reducing burden, they merely delayed it shortly so that they could obtain even more taxation.

By doing so, a constituency of people looking to exempt themselves from increased rates ended up lobbying for exemptions again. In the long run, the revenue gained was neutral, but it was temporally shifted forward to allow agents of the government to extract more now in exchange for less later under the illusion of this being a more permanent arrangement.

Overall, the work within the government has the goal of putting up a smokescreen in front of accountability. Instead of lesser distortions associated with a broadened base as was claimed by these agents, the opposite occurred.

This paper is a good primer to understanding public choice theory, something I’ve briefly written about in another article. Ultimately, it tells an interesting story of how when one strips away the romantic illusions associated with government, one sees a challenge. A situation where many agents act in ways that run directly counter to whatever concept of the public good that they define. Though, this paper suffers from being a pretty specific example, one that is tax-policy dense. As a result, this was a little hard to understand and get through.

Potential Improvements on Dealing with Principal-Agent Problems

Despite principal-agent problems being difficult, occasionally there are solutions that can improve outcomes. In Agency-and-Institutional Theory Explanations: The Case of Retail Sales Compensation, Eisenhardt look at retail sales and finds that compensation policies largely match what a principal-agent theory would predict, that harder to monitor positions are given incentives to perform well, and easier to monitor positions are salaried and monitored more effectively.

The hypotheses set out before the experiment looked at the sort of compensation schemes attached to specific jobs. The agency model proved to be approximately 80% predictive, and when combined with an institutional model, it managed to go up to 87% accuracy (Eisenhardt 503). This was a strong empirical look that examined how firms try to deal with the principal agent problem, and finds most people satisfied with the interventions.

Several monitoring strategies were introduced for cashiers, because the costs of monitoring were low. Yet, those in sales were often better motivated by commissions, which align the incentives of the agent and the employer.

This paper shows that people manage to implement solutions to the theoretical problem of principal-agent situations that work. After all, people are content with them. Though, it is hard to tell whether these solutions are the best solutions, or simply improvements upon a problem. Furthermore, by only looking at commissions, it limits the scope of solutions on this topic area, making it hard to understand whether this is the best, or simply a good option.

Limitations on Applying the Principal-Agent Problem

The principal agent methodology and setup can sometimes fail to hold, even in situations where one might expect people to maximize their own well-being. This seems odd. Why would people avoid accepting a reward for doing something good? Are there limits in terms of motivation regarding helping oneself?

The incentive intensity puzzle may be an important qualification to understanding of the principal agent model and problem. If agents are opportunistic, and try to use strong material incentives to do things, why do people often do the exact opposite of what their incentives push them to do?

A couple examples from “Pride and Prejudice: The Human Side of Incentive Theory“ come up that seem to challenge the assumptions of the principal-agent problem being ubiquitous to human action.

The first example, compensating people for giving blood, demonstrates that altruistic people are less likely to donate blood if financial incentive is provided (partially because materialistic types might jump on the bandwagon, weakening the signaling value (virtue signalling anybody?)).

The second example looks at parents who pick up their children late from daycare. Adding fines for parents who pick their kids up late has the counterintuitive property of encouraging parents to come late. This may appear to be a result of moving from a social obligation mindsight to a market mindset.

The final example demonstrates how high wages, even being above equilibrium rates, seem to have good results. This could be because high wages are an example and signal of higher social expectations.

These examples in conjunction showcase how applied psychology and complex social interactions exist within the world of economics. This paper builds on exploring the limitations of the topic area, and is worth thinking about. However, this paper is primarily a literature review and without its own experimental data, it could simply be cherry-picking a pattern that aligns with intuition.

One thought on “Understanding Principal-Agent Problems”